INTRODUCTION

The greatest charitable work Is teaching people to help themselves. Our Self-Help projects teach, encourage, and empower people to live better in their native country. We have compassion for the suffering of poor people and we help them lift themselves up, to achieve a better life at home. Scroll down for STRATEGIC ALLIANCE.

OUR STORY

Brenda and I have been involved with charity work in Mexico since 2004, and founded Miracle Airlift ten years later. Working with native volunteers, in the Baja Peninsula and the Sierra Madre Occidental, is an experience with a view… the better side of human nature. Volunteers paid their share of expenses and brought along whatever extra they could afford. It wasn’t much, since they are only “slightly less poor” than the people they help. Yet, we’ve seen them give away their own shirts and shoes. Strangely, it seems that poorer people are more generous. This has been an ongoing experience that demolished my earlier notions about Mexico, and its people.

OUR STRATEGIC ALLIANCE

In 2013–14 we founded two organizations, Miracle Airlift, Inc. and Milagro de Volar, A.C., one on each side of the U.S./México border. The two organizations form an international strategic alliance. That enables us to recruit and organize native volunteers throughout México, while legally operating under a banner that encourages trust. Milagro de Volar is staffed with our most capable volunteers and registered as a nonprofit civil association in Mexico. Their principal functions are to recruit volunteers, assist fielding projects, and interface with various agencies of the Mexican government. Through Milagro de Volar, we now have a Native Volunteer Worker Network of about 500 people available in several states throughout México. Our organizations cooperate at arms length. We have no officers or board members in common. Each organization is self-supporting and independent. Being on equal footing, we enjoy the benefits of our individual capabilities and our combined effort is much more effective than either one operating alone. With several hundred volunteers in various parts of the country, we are poised to bring aid into remote areas of Mexico.

OUR VOLUNTEERS

There’s a large pool of enthusiastic volunteers in Mexico. Their finest attributes are knowledge of their country and culture, good attitude, professional skills, and eagerness to work. Three crucial things are required: organization, effective leadership, and ability to travel. They’re making a sincere effort, and we provide the things they need; materials, training, and transportation (never money). Their selfless action, to improve living conditions in their own country, places them on high moral ground. Their example was our inspiration to start up two charities, which became “Miracle Airlift” and “Milagro de Volar”.

DOING THE RIGHT THING

Miracle Airlift at work – What’s Up?

We’re working in Tijuana and Tecate on several projects. With a modest amount of funding we will be able to consider more students as candidates for tuition aid in the Hair Brigade Project. To balance our vocational training, we plan to offer training in welding. We’re working on a local project to operate a breakfast kitchen for primary school kids. We’ve purchased a custom-built industrial grade stove for that project, but haven’t got a permanent site. We rebuilt a small church that was knocked flat and completely destroyed by a windstorm. The former structure was all plywood, with no foundation. Miracle Airlift provided many bags of cement, a truckload of sand, stacks of concrete blocks, and steel re-bar. Milagro de Volar provided the muscle, and skilled workers. A photo gallery of the completed project (Rebuilding Renacer) is on the PROJECTS page. Finally, we are starting a project to build a home of refuge for the old or infirm, on recently acquired land near Tecate.

Why We Must Work in Remote Areas…

Among the natural resources of Mexico are heavy metals, mined in the mountains of the Sierra Madre. But there is an occupational health hazard in these mines that has continued for more than a hundred years. Lung cancer is endemic in miners exposed to Radon, typically because the mine ventilation is inadequate. The physics has been understood since the early 1900’s and the actions taken to protect miners have been routine since the mid 1940’s. The hazard is well understood and disease is preventable. For that reason, there is no excuse for these these deaths to continue. We have a project planned to combat the problem, and you can learn more about this project at Death Sentence. This is much more than a self-help project to improve lives, This is a life-saving project, our most important work.

S T R E T C H I N G Our Range

Long haul buses are common in Mexico, reaching every major city and many smaller ones. Is this good for long distance trips? Probably not. We must reach into remote areas, bringing volunteer doctors who are very limited for time. And when we get near the final destination, we need to get off the bus. “Near” is a relative term, it could be another hundred miles. From this point to the final destination we must use “local transport” which doesn’t work out so well for time, or team size of more than 4 or 5 people. Remote areas are remote because it’s a challenge to get in and out! In flat land, “remote” means washboard roads that shake the shocks loose in the first 60 miles. If anything else can possibly come loose, it will. Where the land is more nearly vertical, “remote” means a switchback dirt road, winding up a mountainside 6 to 8 thousand feet above sea level. That can take another day or more (in good weather and daylight) in a 4-WD vehicle. Or a mules back, which takes somewhat longer…

SOMETHING ABOUT REMOTE AREAS

Compared to the city, remote areas are like another planet and almost as difficult to reach. People in remote areas have serious needs. Medical care tops the list. Our local volunteers have made few visits to remote areas, because their ability to travel is limited. Therefore, the keystone of our mission is “to help the helpers” which includes providing transportation for volunteer workers. Our professional volunteers, mainly physicians, are limited by time. Usually the most they can give is 3 days, which means they need to fly.

4WD Jeep – Carried us over the summit.

Click or touch the photo

A full day’s drive up the mountain, and we arrived before dusk. I thought this was pretty good, until our guide said we needed an early start in the morning. Our destination was on the other side, over the summit. The next day was less arduous, and we arrived at the rancho in mid afternoon. But check out the two mules…

Mules – Arrived two days later, by themselves!

Click or touch the photo

They carried a rider and a load of packages down the mountain to the city below. The rider delivered the packages, but stayed in the city. He “returned” the mules to their owner by releasing them on the road at the base of the mountain. They arrived at home on their own, two days later, at the rancho we were visiting. Smart critters! Maybe they took a shortcut…

BIGGER Than You Think, AND Thinking BETTER

México is a big place, there are commercial airports and jet airliners flying throughout the country. Whenever we have volunteers who live relatively close to a target area we enlist them. Those who travel more than 600 miles go by air. Miracle Airlift pays for the tickets because their work is worth more than the ticket and our strength is in the hands of our volunteers. Their time is limited, we maximize their working days per trip by minimizing travel time.

GETTING OFF THE GROUND

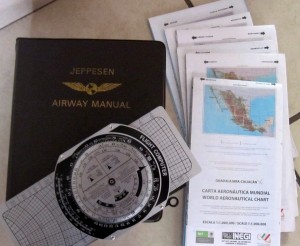

The most challenging part of any trip to a remote area is the last leg. Experience and local volunteers have taught us the hazards of ground travel in remote areas. Locals don’t travel after dark. They stay overnight in a populated place of refuge. Their example is wisdom. Any location that can’t be reached in daylight is ruled out. This may be tricky, because shadow effects in the mountains can cause a rapid onset of darkness. “Local transport” on the ground can only carry a few people and it can take a day or more just to get up the mountain, when the road is passable. Storms can cut off mountain roads for weeks. The solution for volunteer medical teams, who are strictly limited for time, is to fly. An airplane can quickly shuttle back and forth between a commercial airport and a remote airstrip to bring in the team. Many remote “ejidos” (common land communities) have a nearby airstrip, and the same is true of mountain mining communities. These aeronautical charts (see photo) show hundreds of small airstrips all over México. Most are unpaved, but good enough for capable light airplanes.

transport” on the ground can only carry a few people and it can take a day or more just to get up the mountain, when the road is passable. Storms can cut off mountain roads for weeks. The solution for volunteer medical teams, who are strictly limited for time, is to fly. An airplane can quickly shuttle back and forth between a commercial airport and a remote airstrip to bring in the team. Many remote “ejidos” (common land communities) have a nearby airstrip, and the same is true of mountain mining communities. These aeronautical charts (see photo) show hundreds of small airstrips all over México. Most are unpaved, but good enough for capable light airplanes.

Local bush pilots occasionally serve some remote airstrips. On an early fact-finding trip in the Sierra Madre, two volunteers were aboard a bush plane for a 25-minute flight, and neither of them wants to repeat the experience. One was seated next to an open doorway, because the door was missing. He had no seat belt and his seat was loose, because it wasn’t bolted to the floor. He had a windy flight maintaining a white-knuckle grip on the seat in front of him. Minutes after takeoff the (single) engine quit. Obviously it restarted. In my opinion, poor maintenance and pilot judgement are likely reasons that bush flights have a poor safety record. Local people shrug it off with “así es la vida.” I don’t. The suggestion of a Mexican colleague “we can just pay a bush pilot” – in a word, is not going to fly.

Turbo Aztec w/STOL

In the beginning, we realized an airplane is necessary to serve remote areas, which inspired our chosen name(s). But the fact-finding bush flight really sharpened our focus!

Twin-engine airplanes are desirable for their extra margin of safety, especially over mountains where loss of power in a single-engine airplane is unpleasant to contemplate. The failure of one engine in a twin is an In-flight emergency, but not necessarily a disaster. So, are twin-engine planes better than single-engine planes? It depends… Twins have their own unique issues. For example, even simple operations like takeoff are more complicated. Safe takeoff in a turbo Aztec requires enough runway to accelerate to takeoff speed, then brake to a stop. On a paved, sea-level runway, that’s more than double the distance required just to lift off the ground. Mountain airstrips are thousands of feet above sea level, where the reduced density air requires additional runway. Add some more to allow for the poor braking characteristics on dirt. Total required runway for takeoff, a minimum of two and a half times the runway length required for landing. Actual length may vary and is calculated shortly prior to takeoff to account for variables: temperature, altitude, takeoff weight, wind, and runway surface. Some airstrips in the region will be off-limits and unavailable to us, if we fly a conventional twin. A center line of thrust twin, specially modified with bigger engines, is an exception. In a conventional twin we would use a longer airstrip “in the neighborhood” and then take local ground transport to our final destination.

The point of this discussion is not as much about twins vs singles, as it is about safety as a function of engine reliability. It depends… on the mission. Two engines may be “better” than one, but not always. Turbine engines are highly reliable, more so than piston engines, because a turbine has a lot less moving parts. And they’re very powerful. A “STOL” airplane with a single turbine that’s 50% more powerful than both of the Aztec’s engines, carries a heavier load and uses perhaps 1/3 of the runway required by the Aztec, is a very capable airplane. If money was not an issue, a single turbine airplane would be an easy first choice for our work. There are perhaps three to five suitable models from different manufacturers, on the market.

Kodiak – by Quest Aircraft

Quest Aircraft specifically designed the Kodiak as a “STOL” airplane for remote area work. Think of a 4×4 pick-up truck, with wings. The Kodiak can safely land and take off from any airstrip we could find on Mexican charts. The Kodiak’s highly reliable turbine engine will run two to three thousand hours longer between overhauls than the Aztec’s piston engines. We would love to have a Kodiak, and we believe in Miracles. A turbine powered PC-6 Porter is less elegant but would be perfect for us, if we could find one at an affordable price. Lowering the bar, a turbocharged piston twin with center-line thrust would be a more affordable alternative. Relatively few of these have been modified with bigger engines, capable of safely continuing a takeoff on just one of the engines. That would be a reason to buy one. However, a Turbo Aztec carries a bigger load, and is a realistic goal for planning purposes…

Depending on the airplane, teams may need to be transported by “Airlift”, which implies shuttling back and forth between a remote airstrip and a large metropolitan airport with a bigger team than we could carry in one trip. The airplane in the photo below looks pretty, but it’s unsafe for short, high-altitude mountain airstrips. Please help us buy an airplane that can do the job! Sign up for an automatic monthly donation of any amount. You may use the CONTACT form to earmark your donations for the airplane fund.